- Discover, Explore, Connect, Debate…

- These themes – with on-camera comments from the film, selected written texts and related resources as starting points for discussion – connect us to Baldwin’s larger world, to the complex web of events and ideas from which he came. A world of prejudice, possibility and gradual progress, these were the dynamics that shaped Baldwin’s writings, that shaped our film’s contents … and that are now in the process of shaping us.

- A better understanding of our past will help us grow a better future.

- Jimmy's Pulpit-

Discussion Topics & Themes

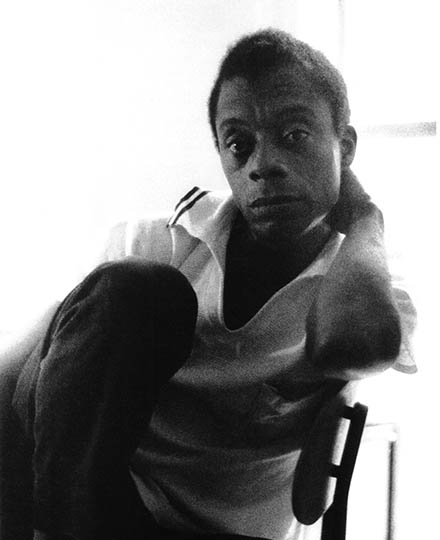

Photo: George E. Joseph

2. Racism

3. Human Rights

4. The Continuum of Literature

5. The Role of Art in Social Change

- African-American History: From the slave narrative to early 20th-century Harlem, from segregated America to the Civil Rights movement and beyond, Baldwin’s journey through history is up close and personal.

- Racism: Baldwin was both acutely aware of and shockingly eloquent about racial prejudice and social injustice, whether in America or abroad.

- Human Rights: For Baldwin, freedom transcended issues of race, gender, religion, politics … and began with brotherhood.

- The Continuum of Literature: Baldwin’s novels, essays, short stories and plays are part of a much larger literary context.

- The Role of Art in Social Change: Like many artists throughout history, Baldwin had to balance artistic development with the demands of his time.

- Organized Religion & Explorations of Faith: The son of a Baptist minister, Baldwin spent three years as a teenage preacher, then left the church to become a Biblically-influenced writer and a lifelong secular preacher. His time in Turkey gave him an appreciation of other faiths and “non-Western Gods.”

- Homosexuality: Baldwin was one of the first American writers to confront homosexuality with unexpected honesty.

- Black Masculinity: Black men still struggle with issues of one-dimensional stereotypes, negative role models and dashed aspirations. Baldwin explored these stereotypes in his writing – and had the courage to break with them in his personal life.

- Self-Imposed Exile: Baldwin spent years of his life as an expatriate: in Paris; in a remote Alpine village in Switzerland; in Turkey; and finally, in the home he purchased in Southern France.

- African-American Music: BALDWIN’s soundtrack honors the gospel, jazz and blues music that filled Jimmy’s life – along with searing guitar riffs from Jimi Hendrix to underscore Civil Rights violence, Turkish folk music from his years by the Bosphorus … and the African drums which played at his funeral.

- Criticism of Baldwin & Changing Interpretations: As it is for many successful writers, Baldwin’s fame was fraught with painful expectations and frequent criticism.

- Human Progress, Hope and the Limits of Change: Baldwin railed against injustice, prejudice – and the glacial pace of reform – but he never lost hope.

Dr. Maya Angelou: “We became friends in the late 50's: just as the United States was poised to make its quantum leap into the future; just as Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks and other Southerners were girding themselves for the second civil war in one hundred years; and just when Malcolm X was giving voice to the anger in the streets and in the minds of northern black city folks.”

James Baldwin: “Between two or three weeks ago, I had to fly from Hollywood to New York to do a benefit with Martin at Carnegie Hall. I did not have a suit and had one fitted for me that afternoon. I wore the same suit at his funeral. What can I say? Medgar, Malcolm, Martin, murdered. I really cannot talk -- and yet I must.”

James Baldwin: “It comes as a great shock around the age of five or six or seven to discover that the flag to which you have pledged allegiance, along with everybody else, has not pledged allegiance to you. It comes as a great shock to discover that Gary Cooper killing off the Indians, when you were rooting for Gary Cooper, that the Indians were you. It comes as a great shock to discover that the country which is your birthplace, and to which you owe your life and your identity, has not in its whole system of reality evolved any place for you.”

Dr. Maya Angelou: “France was not without its race prejudices. It simply didn't have any guilt vis-à-vis black Americans. And black Americans who went there, from Richard Wright to Sidney Bechet, were so colorful and so talented and so marvelous and so exotic-- Who wouldn't want them? Of course. But among the people they did not want in France were the Algerians. As Jimmy said, they were the niggers of France. To him, they were his brothers. He was very outspoken during the Algerian War, when they had been trying to win their freedom from France in the 50's. He wrote about the Algerians in NO NAME IN THE STREET.”

James Baldwin: “It's up to you. As long as you think you're white, there is no hope for you. As long as you think you're white, I'm going to be forced to think I'm black.”

Amiri Baraka: “He brought that cry into the cocktail parties, as well as the universities, as well as the streets.”

James Baldwin: “It is not a romantic matter. It is the unalterable truth: all men are brothers. That's the bottom line. If you can't take it from there, you can't take it at all.”

James Baldwin: “You think your pain and your heartbreak are unprecedented in the history of the world. But then you read. It was books that taught me, that the things that tormented me the most were the very things that connected me with all the people who were alive, who have ever been alive.”

Dr. Maya Angelou: “I hear Baldwin as a part of the continuity, begun if you will for me anyway, with Frederick Douglass in 1849 in the slave narrative. I hear his voice. I hear Baldwin when I think of Jupiter Hammon, a slave in the 18th century. I hear Baldwin in the music, the lyric really, of George Moses Horton, writing about 1840, '50. He wrote 'Alas, and was I born for this, to wear this slavish chain--' I hear Baldwin.”

David Leeming: “I think it's important to realize that rhetorically the church is extremely important to Jimmy, the lang¬uage of the church, the language of the Bible primarily, the patterns of the Bible, even the struggles of the Bible.”

Yasar Kemal: “My favorite book of his was ANOTHER COUNTRY. Jimmy and I talked a lot about that book – and about the theory of novels. We talked about Dostoyevsky, and Faulkner. We both liked Dostoyevsky. His philosophy was like Jimmy's: he was not a pessimist. In book after book, he would pile darkness upon darkness – and then blast you with light.”

Ishmael Reed: “James Baldwin gave black people an example. I know he inspired me to write. When you see another black person out there writing, when all you've been fed is Milton and Shelley, and all these people who were dead 200 years ago, that gets your attention.”

James Baldwin: “There are days, and this is one of them, when you wonder: what your role is in this country, and what your future is in it.”

William Styron: “In the time that he was here, I first began to see that terrific almost schizoid wrenching that he suffered. Being pulled in one direction by the demands of his art and in the other direction by his moral need to do what he was also good at, which was to preach. That is to preach the Gospel of Equality, to preach the Gospel of Revolution if you want to call it that.”

CBS-TV Interviewer: “Mr. Baldwin -- Do you think you'll ever write anything that doesn't have a message?

James Baldwin: “I don't quite know what that means. In my view, no writer who ever lived could've written a line without a message. It depends on -- what you're asking me, I think -- to what extent do I intend to become a polemicist or a propagandist. Well, I can't answer that, because the nature of our situation has imposed on everybody involved in it things one wouldn't ordinarily do. You take risks which you wouldn't ordinarily take.”

James Baldwin: “I had been a boy preacher for three years. And those three years in the pulpit, I didn't realize it then, but that is what turned me into a writer, really. Dealing with all that anguish and that despair, and that beauty for those three years. And I left because I didn't want to cheat my congregation. I knew that I didn't know anything at all. And I couldn't leave, if I left the pulpit I had to leave home. So I left the pulpit and I left home in the same day. That was quite a day.”

James Baldwin: “I don't know if white Christians hate Negroes or not; I know that we have a Christian church which is white and a Christian church which is black. I know as Malcolm X once put it, the most segregated hour in American life is high noon on Sunday. That says a great deal to me about a Christian nation. It means that I can't afford to trust most white Christians, and certainly cannot trust the Christian church.”

David Leeming: “He once said that he left the pulpit in order to preach the Gospel and in a certain sense that's true. This was something he could do. You could say this was God's gift to him and this is what he made use of.”

James Baldwin: “The trick is to say ‘yes’ to life. It's only this weird twentieth century which is so obsessed with the particular details of anybody's sex life. I don't think those details make any difference, and I will never be able to deny a certain power that I have had to deal with, which has dealt with me, which is called love -- and love comes in very strange packages. I've loved a few men, I've loved a few women. And a few people have loved me. That's all that has saved my life.”

Novelist / Reviewer Nelson Algren [about GIOVANNI’S ROOM]: "This novel is more than another report on homosexuality. It is the story of a man who could not make up his mind, one who could not say ‘yes’ to life. It is a glimpse into the special hell of Genet – Jean Genet, the French homosexual writer – told with a driving intensity, its horror sustained all the way."

James Baldwin [about his father]: “Part of his problem was he couldn't feed his kids. But I was a kid and I didn't know that and he was very religious, very rigid. In fact, in a word, he wanted power. He wanted Negroes to do in effect what he imagined white people did, that is to have, to own the houses, to own U.S. Steel, and this is what in effect killed him. Because there was something in him which could not bend. He could only be broken.”

James Briggs Murray [about Cleaver’s SOUL ON ICE]: “Many of us equated the black revolution with our manhood, with militancy and masculinity. And here was Eldridge Cleaver saying that Jimmy Baldwin hated his blackness, and hated his masculinity.”

Dr. Maya Angelou: “In this particular society, we are supposed to be so contained. Men are supposed to be men. Women are supposed to be women, and not need, really need, anybody. The ability to ask "Will you be my brother?" -- the courage to ask -- is often missing. James Baldwin was a brother. Incredible!”

James Baldwin: “The best thing I ever did with my life, I think, was flee America and go to Paris in 1948. It gave me time to vomit up a great deal, a great deal of bitterness. At least I could operate in Paris without being menaced socially. No one cared what I did.”

David Leeming: “He never lost sight of the fact that he was an American. He always considered himself very much an American. You can see that in his early essays, the NOTES OF A NATIVE SON essays. In which really he is using Paris, using France, as a means of discovering his own identity.”

James Baldwin [about living in Turkey]: “It was a place to rest and to work. Because I couldn't live in Paris anymore, and New York was impossible. And it was in some ways another way of life, another set of assumptions -- which are not mine, which I didn't grow up with because I'm not a Muslim … but which can teach you a great deal about your own set of assumptions because they are -- Once you find yourself in another civilization, you are forced to examine your own.”

James Baldwin: “In that chalet in the snow, I listened to Bessie Smith and to Fats Waller and they carried me back to what I myself had been like when I was a little boy -- and gave me the key to the language which gave me GO TELL IT ON THE MOUNTAIN.”

Bobby Short: “We talked a lot about the churches in Harlem, and the music in the churches. And sometimes we'd be full of red wine and sit down at the piano, and I'd knock out those songs and David and Jimmy and I and Bernard would sing ‘Hide Me in Thy Bosom,’ or ‘Have a Little Talk with Jesus.’"

Interviewer: “Do you think you'll ever write anything without a message?”

Reviewer: Far too much sermonizing...

Interviewer: “You do spend a long time between novels. Why is that?”

Reviewer: Too much time in Turkey and France…

Interviewer: “Are you still in despair about the world?”

Dr. Maya Angelou: “Jimmy was not bitter. What Jimmy was, was angry. He was constantly-- He was angry at injustice, at ignorance, at exploitation, at stupidity, at vulgarity. Yes, he was angry.”

James Baldwin: “What is it you want me to reconcile myself to? I was born here almost sixty years ago. I'm not going to live another sixty years. You always told me it takes time. It has taken my father's time, my mother's time, my uncle's time, my brothers' and my sisters' time, my nieces' and my nephews' time. How much time do you want for your ‘progress’?”

James Baldwin: “Love has never been a popular movement. And no one's ever wanted, really, to be free. The world is held together, really it is held together, by the love and the passion of a very few people.”

James Baldwin: “But I don't think I'm in despair. I can't afford despair. I can't tell my nephew, my niece-- You can't tell the children there's no hope.”

James Baldwin: “The day will come when you will trust you more than you do now, and you will trust me more than you do now. And we can trust each other. I do believe, I really do believe in the New Jerusalem, I really do believe that we can all become better than we are. I know we can. But the price is enormous, and people are not yet willing to pay it.”

. . . . . . .